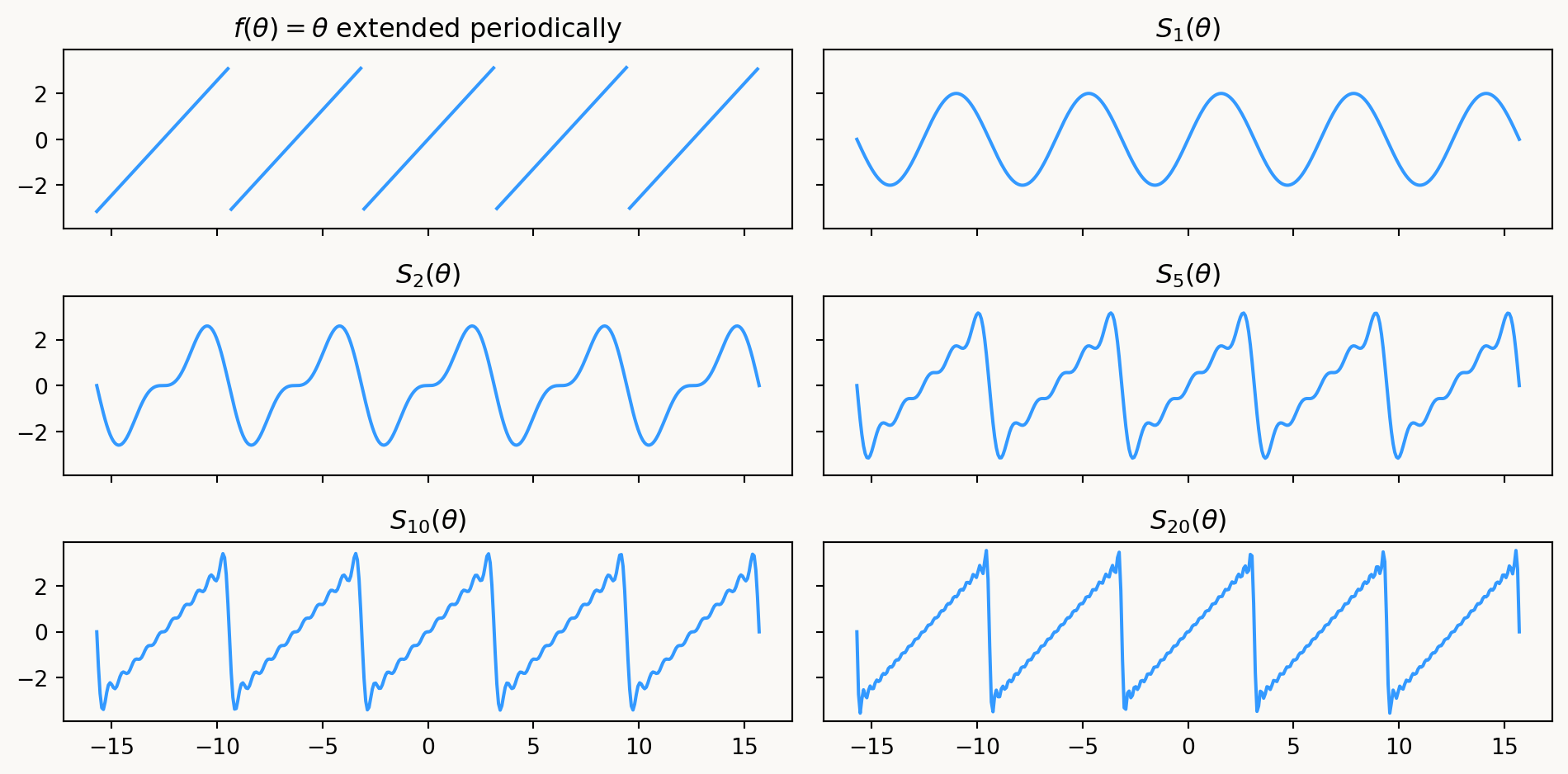

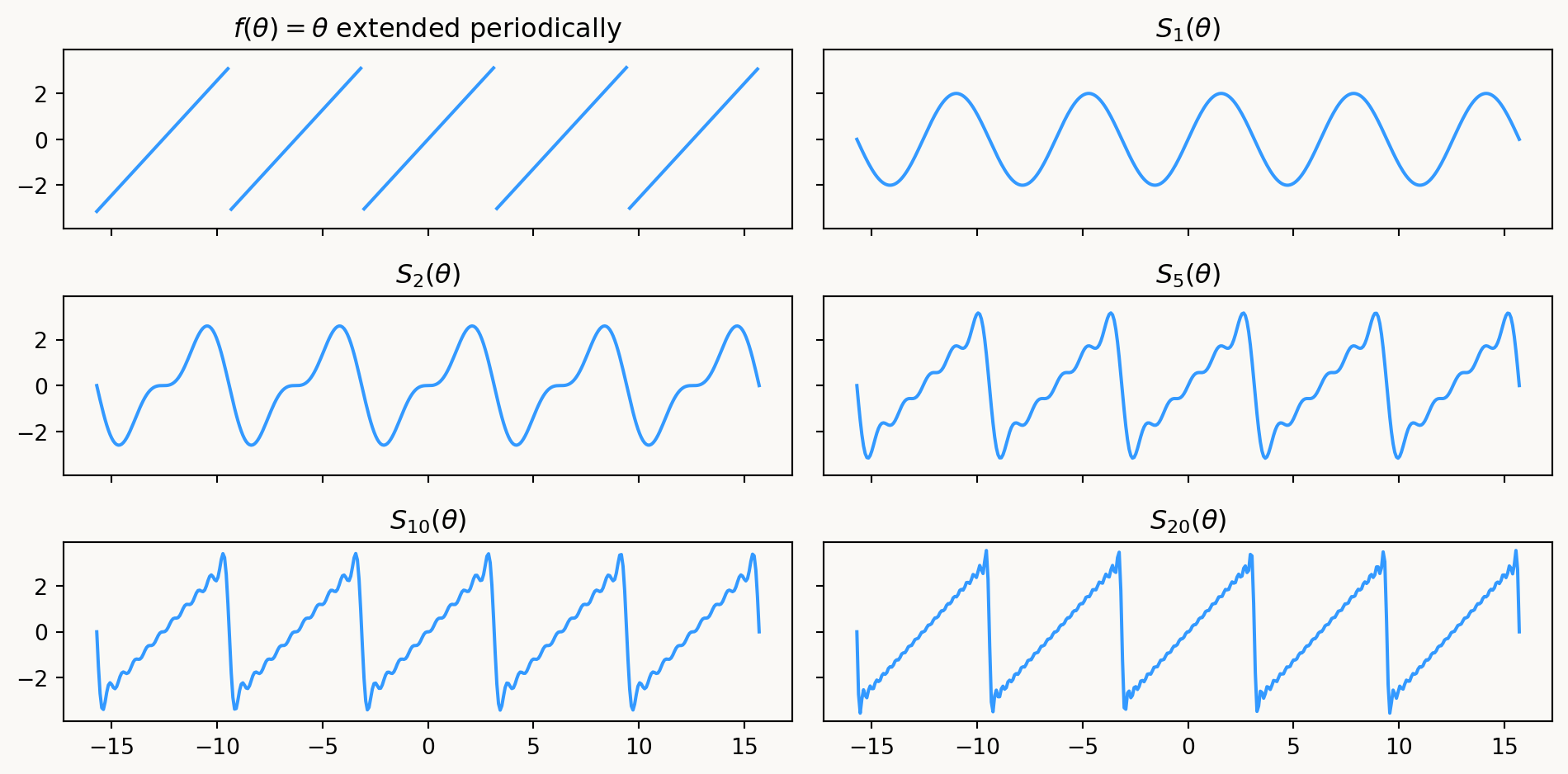

Define the function \(f(\theta) = \theta\) for \(\theta \in [-\pi, \pi]\), and extend it to a function on \(\mathbb{R}\) with period \(2\pi\). Compute the Fourier coefficients and series of \(f\).

Theorem (Bessel’s inequality — \(c\)-version).

If \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{C}\) is a \(2\pi\)-periodic function, integrable on \([-\pi, \pi]\), and if \(c_n\) are its Fourier coefficients, then

\[ \sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty |c_n|^2 \leq \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^\pi |f(\theta)|^2 \, d\theta. \]

Theorem (Bessel’s inequality — \(c\)-version).

If \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{C}\) is a \(2\pi\)-periodic function, integrable on \([-\pi, \pi]\), and if \(c_n\) are its Fourier coefficients, then

\[ \sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty |c_n|^2 \leq \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^\pi |f(\theta)|^2 \, d\theta. \]

Begin with the basic observation that \(|z|^2 = z \overline{z}\) for any complex number \(z\).

Applying this to \(z = f(\theta) - \sum_{n=-N}^N c_n e^{in\theta}\), we have \[ \left| f(\theta) - \sum_{n=-N}^N c_n e^{in\theta} \right|^2 = \left( f(\theta) - \sum_{n=-N}^N c_n e^{in\theta} \right) \overline{\left( f(\theta) - \sum_{n=-N}^N c_n e^{in\theta} \right)} = \left( f(\theta) - \sum_{n=-N}^N c_n e^{in\theta} \right) \left( \overline{f(\theta)} - \sum_{n=-N}^N \overline{c_n} e^{-in\theta}\right). \]

Expanding the right-hand side, we have \[ \left| f(\theta) - \sum_{n=-N}^N c_n e^{in\theta} \right|^2 = |f(\theta)|^2 - \sum_{n=-N}^N c_n \overline{f(\theta)} e^{in\theta} - \sum_{n=-N}^N \overline{c_n} f(\theta) e^{-in\theta} + \sum_{n=-N}^N \sum_{m=-N}^N c_n \overline{c_m} e^{i(n-m)\theta}. \]

Divide both sides by \(2\pi\), integrate from \(-\pi\) to \(\pi\), and recall that: \[ \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^\pi f(\theta) e^{-in\theta} \, d\theta = c_n, \quad \text{and} \quad \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^\pi e^{i(n-m)\theta} \, d\theta = \begin{cases} 1 & : n=m, \\ 0 & : n \neq m. \end{cases} \]

We get \[ \begin{align*} \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^\pi \left| f(\theta) - \sum_{n=-N}^N c_n e^{in\theta} \right|^2 \, d\theta &= \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^\pi |f(\theta)|^2 \, d\theta - \sum_{n=-N}^N \left( c_n \overline{c_n} + \overline{c_n} c_n \right) + \sum_{n=-N}^N c_n \overline{c_n} \\ &= \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^\pi |f(\theta)|^2 \, d\theta - \sum_{n=-N}^N |c_n|^2. \end{align*} \]

But the left-hand side is non-negative, so we have \[ \sum_{n=-N}^N |c_n|^2 \leq \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^\pi |f(\theta)|^2 \, d\theta, \] for each \(N\). Now let \(N\to \infty\). Q.E.D.

Theorem (Bessel’s inequality — \(ab\)-version).

If \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{C}\) is a \(2\pi\)-periodic function, integrable on \([-\pi, \pi]\), and if \(a_n\) and \(b_n\) are its Fourier coefficients, then \[ \frac{|a_0|^2}{4} + \frac{1}{2}\sum_{n=1}^\infty \left( |a_n|^2 + |b_n|^2 \right) \leq \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^\pi |f(\theta)|^2 \, d\theta. \]

Theorem (Riemann-Lebesgue lemma).

If \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{C}\) is a \(2\pi\)-periodic function, integrable on \([-\pi, \pi]\), and if \(a_n\), \(b_n\), and \(c_n\) are its Fourier coefficients, then \[ \lim_{n\to \infty} a_n = \lim_{n\to \infty} b_n = \lim_{n\to \pm \infty} c_n = 0. \]