07 Functions of multiple variables, part 3

Functions as transformations

We may try to visualize a function \(f:\mathbb{R}^m \to \mathbb{R}^n\) via its graph, as we’ve seen.

However, we can also think of \(f\) as a physical transformation of \(\mathbb{R}^m\) into \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

This will allow us to visualize functions all the way up to \(\mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}^3\).

Exercise 1: Functions \(\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) as transformations

Describe the action of the following functions \(\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) as physical transformations of the real line into itself. Draw pictures!

- \(f(x) = x^2\)

- \(g(x) = 2x+1\)

- \(h(x) = -x-1\)

- \(k(x) = x^3\)

- \(j(x) = \sin{x}\)

Exercise 2: Functions \(\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}^2\) as transformations

Describe the action of the following functions \(\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}^2\) as physical transformations of the real line into the plane. Draw pictures!

- \(f(t) = (t, t^2)\)

- \(g(t) = (2t+1, -t)\)

- \(h(t) = (\cos{t}, \sin{t})\)

- \(k(t) = (\sin{t}, \cos{t})\)

- \(j(t) = (t^2, t^3)\)

Exercise 3: Comparison to linear functions, part 1

Compare the function \(j(t) = (t^2, t^3)\) from the previous exercise to the linear function \(L:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}^2\) defined by \(L(t) = (2t-1,3t-2)\) at the point \((1,1)\). Draw pictures!

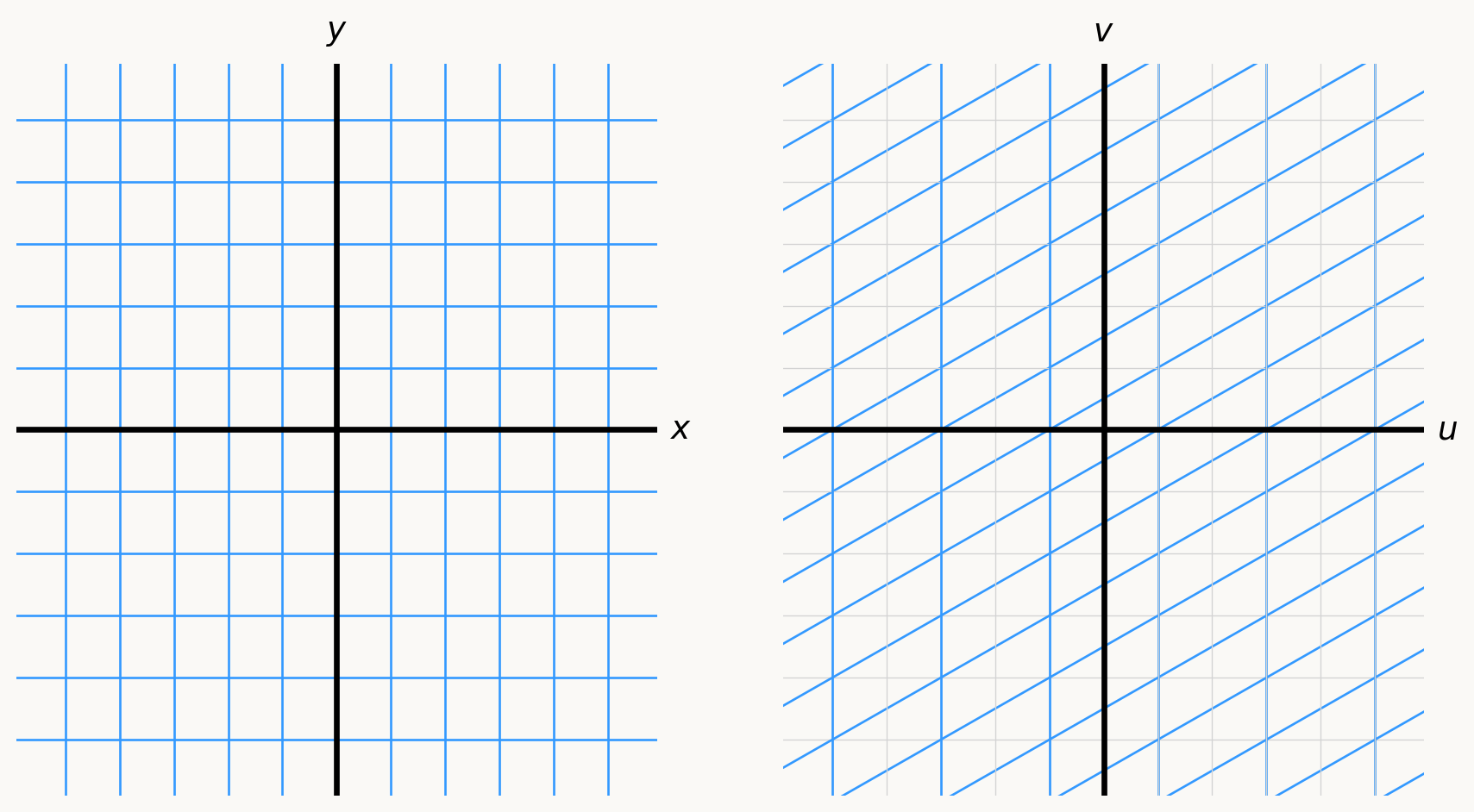

Exercise 4: A linear function \(f:\mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^2\) as a transformation

Define a function \(f:\mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^2\) by \[ (u,v) = f(x,y) = (2x+1, x-y-1). \] Describe the action of \(f\) as a physical transformation of the plane into itself. Draw pictures!

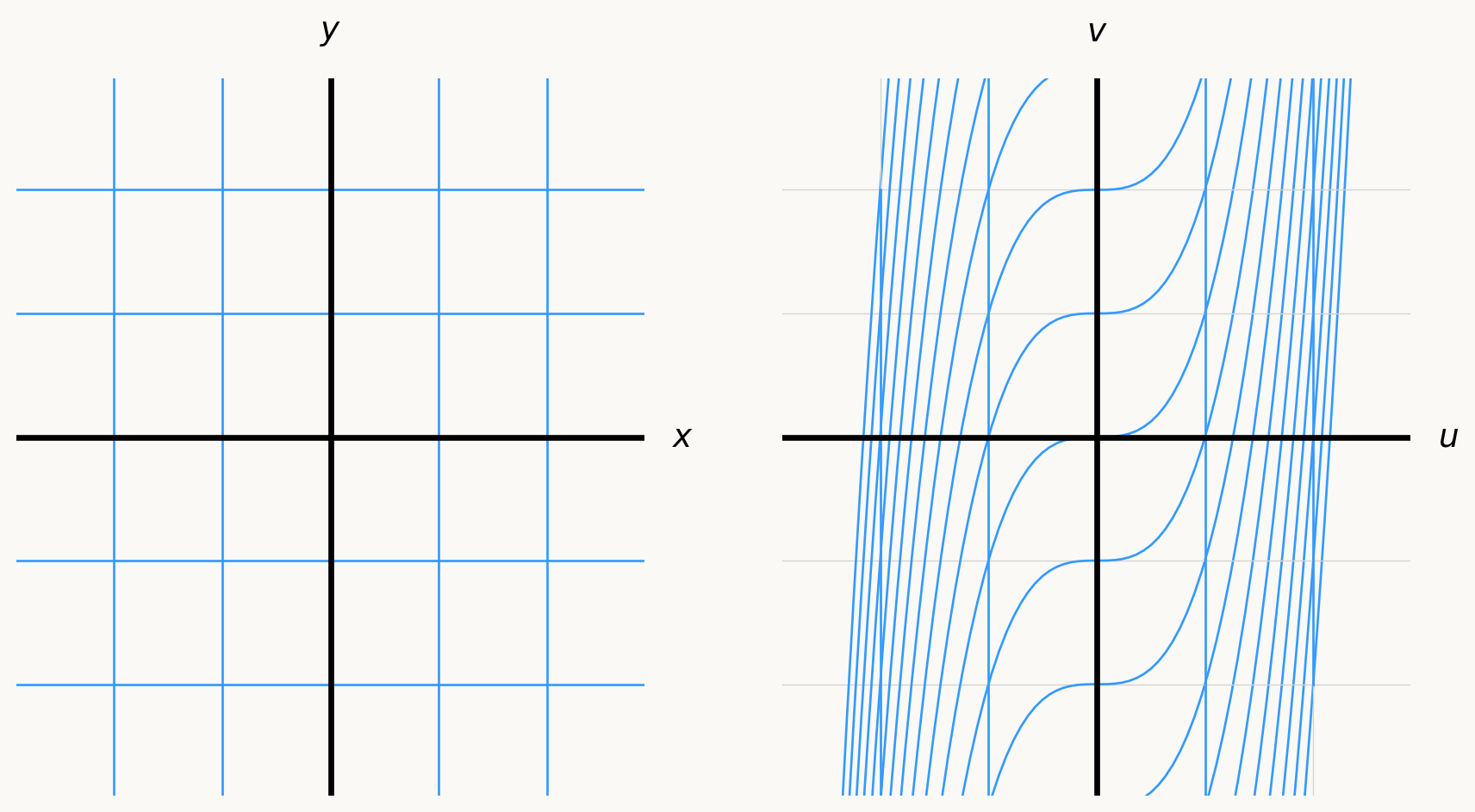

Exercise 5: A nonlinear function \(g:\mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^2\) as a transformation

Define a function \(g:\mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^2\) by \[ (u,v) = g(x,y) = (x, x^3 + y ). \] Describe the action of \(g\) as a physical transformation of the plane into itself. Draw pictures!

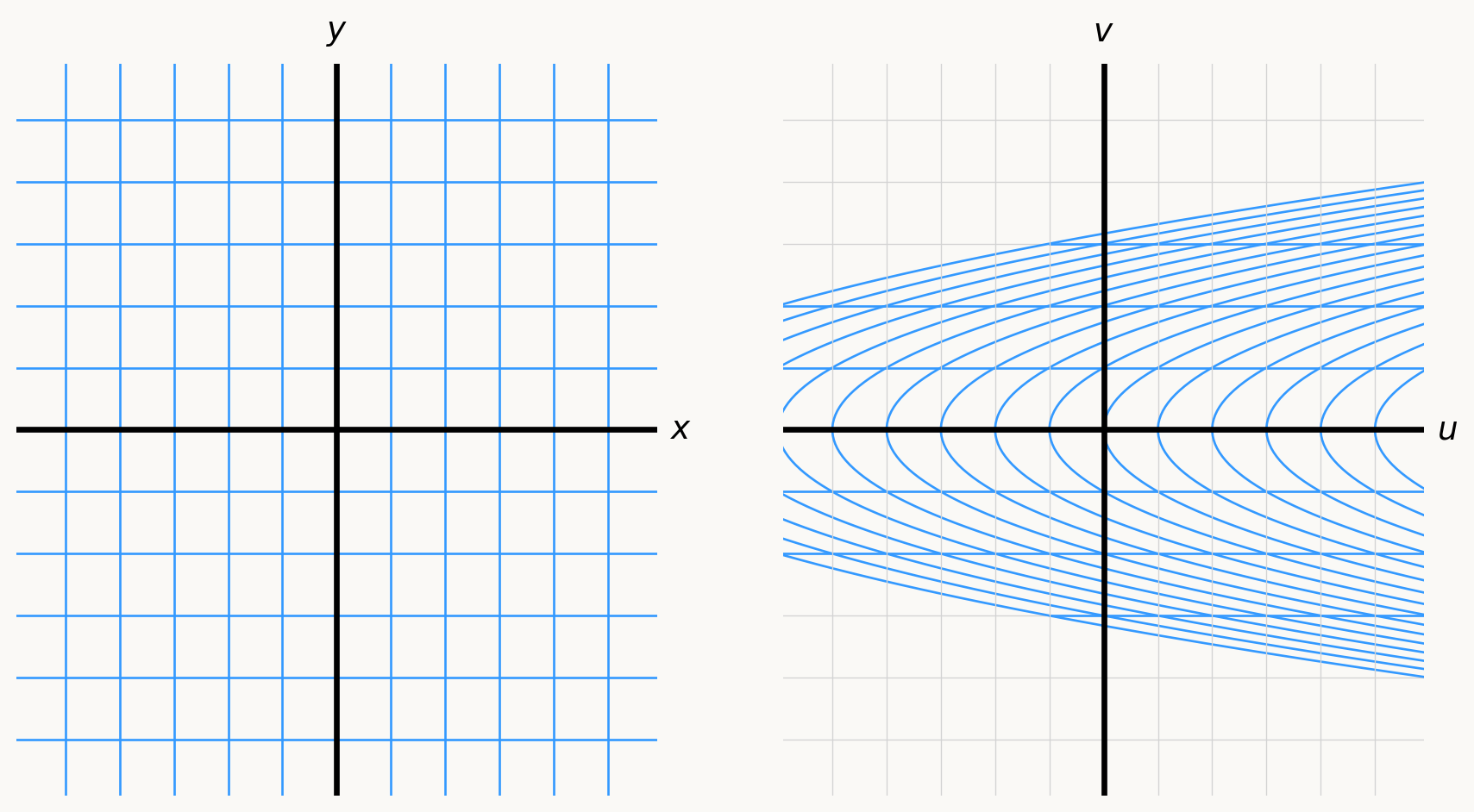

Exercise 6: A nonlinear function \(k:\mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^2\) as a transformation

Define a function \(k:\mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^2\) by \[ (u,v) = k(x,y) = (y^2 +x, y). \] Describe the action of \(k\) as a physical transformation of the plane into itself. Draw pictures!

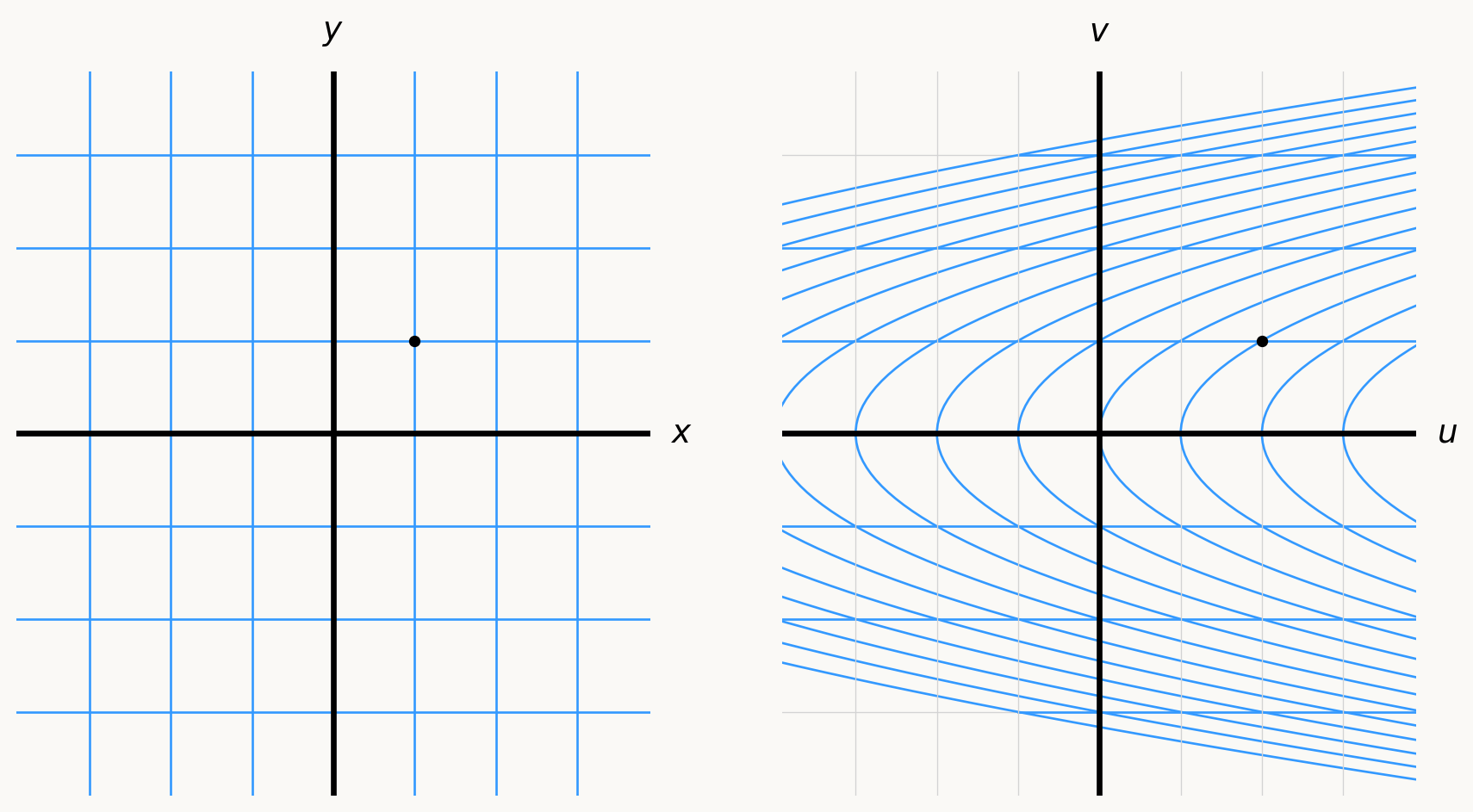

Comparison to linear functions, part 2

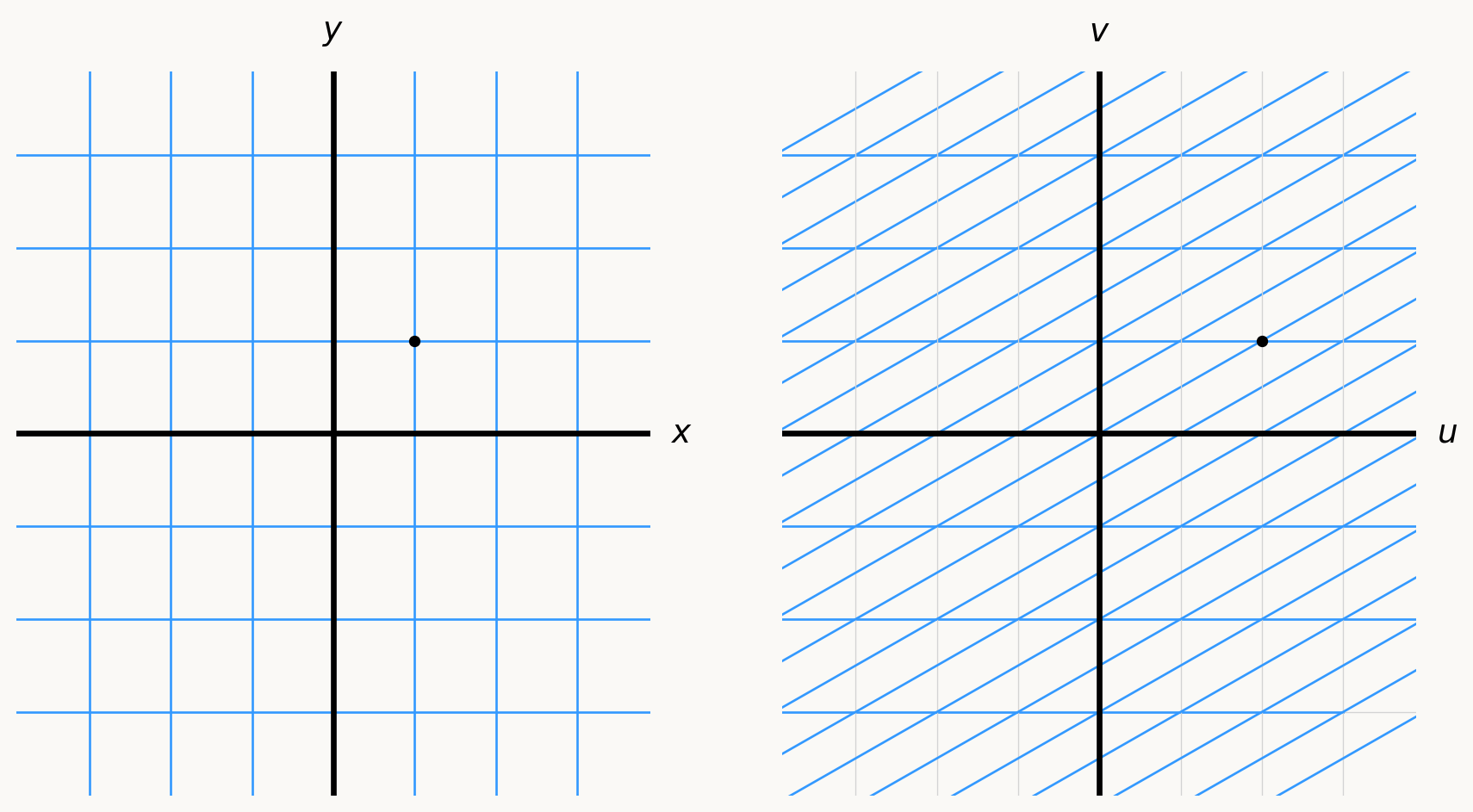

- Return to the function \(k(x,y) = (y^2 + x, y)\), and focus on a point in the \(xy\)-plane, say \((1,1)\), and look at its image in the \(uv\)-plane, which is \((2,1)\):

- Now consider the linear function \(L:\mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^2\) defined by \(L(x,y) = (x+2y-1,y)\), and focus on the same points:

Do you notice how that, if you only compare the graphs in the \(uv\)-plane near the point \((2,1)\), the function \(k\) looks a lot like the linear function \(L\)? That’s because \(L\) is the “best” linear approximation of \(k\) near \((1,1)\), cooked up using the derivative of \(k\) at \((1,1)\).

Same story here as in single-variable calculus. Nothing new conceptually.